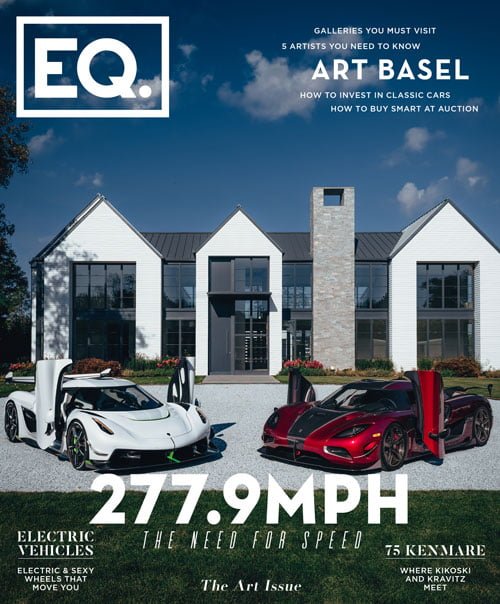

Everyday Excitement

Classic Car Replicas

Written by Jack Williams

In August of 2019, auction house RM Sotheby’s will roll out a classic 1962 Ferrari 250 GT SWB Berlinetta onto the sales blocks at its flagship three-day event, in Monterey, California, with early estimates already predicting the vehicle could fetch anywhere between $8,000,000 and $10,000,000. So coveted are Ferrari 250s of this era–from Berlinettas to Testa Rossas, California Spyders to GTOs–asking prices have continued to rise over recent years, and it seems like every few months a record is broken as fees climb higher and higher into the double-digit millions.

These enormous figures, however, come as no surprise to those in the classic car community, given the rarity of the remaining vehicles from Ferrari’s 1953 to 1964 series of 250s; their individual histories, which range from movie appearances to race wins; and, of course, the incomparable driving experiences they still offer even today.

Let’s take the 250 SWB Berlinetta–only 165 were ever produced from 1959 until 1962, and stories, no doubt, are stamped to each and every one of them. This model of 250 came with the esteemed 3.0 liter, V12 engine that was indicative of Ferrari’s racers at the time. SWB Berlinettas won the 1960, ’61 and ’62 Tour de France Automobile. Heavier steel bodies (around 80-something of them, for street use) and light-weight aluminum versions (for racing) made this the model of choice for 250 “customers [who] were able to win the race on Sunday and drive to the office on Monday, all in the same car,” Marcel Massini, a renowned Ferrari historian who advises the likes of Sotheby’s, told EQ.

But what if such a car can’t be driven to work on Monday by those who wish to do so some 60 years later? What if price points and availability hinder some from ever obtaining, or fear of damage freezes those who are already fortunate enough to own?

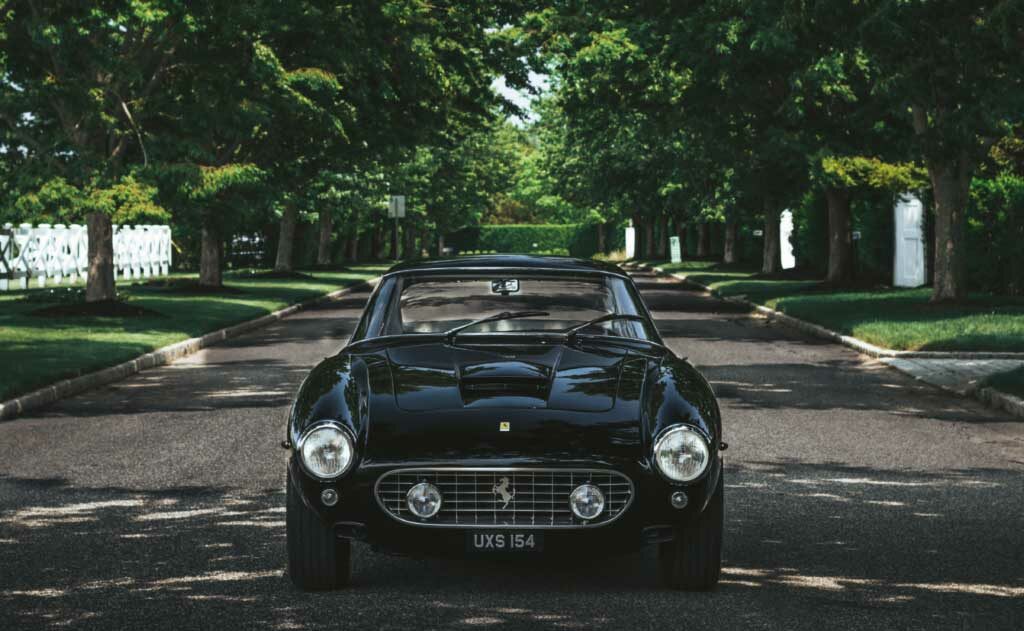

One such vehicle sitting in Manhattan Motorcars, on 11th Avenue in Midtown Manhattan, looks to offer an alternative.

Upon first glance, the gleaming black coupe looks just like any other pristine SWB Berlinetta from decades ago.

Ferrari badge: check.

Iconic body shape:check.

Gear stick, dial positions, steering wheel design: check, check and, well, check.

Price: $1.39 million: Wait, what?

Yes, according to Mark Lyon, whose company GTO Engineering produced the car on show, this model is “nearly 100 percent the same” as the original, and at “one tenth of the price.”

The 250 GTO, as it is named, may have been inspired by 1950s and 60s Italian design, but it was actually constructed by the hands of Brits in 2018. Based in Reading, England, just west of London, GTO Engineering has focused on Ferrari servicing and restoration since it opened in 1994. As Ferrari’s classic models become ever older, parts wear out; replacements become scarce or non-existent. GTO Engineering then steps in to make the new ones themselves — which may mean building, say, a replacement engine from scratch for a customer who wants to take out a valuable original and protect it.

In 2008, however, the global financial crisis hit, impacting GTO Engineer’s forecasts for their traditional work. “I said to my staff, ‘This is going to be a quiet year this year — what do you say to building a whole car?,’” Lyon, whose company has 42 staff in its U.K. headquarters and an operation in Los Angeles, explained. “Everyone liked the idea. So, we started then with a couple of deposits from clients, and started making cars.”

What came next Lyon describes as “very advanced reverse engineering.” Knowing he and his staff had either made or owned all the parts to make up the likes of a short-wheel-base (SWB) Berlinetta, they set to work on making their own version of the car that was as close as possible in looks, performance and feel to the original. That process took around two years from design stage to the finished model, and, to date, the company has made some 28 vintage Ferraris, 22 of which are like the one in Manhattan Motorcars, Lyon said.

On average, three members of staff will now work on each ground-up creation, and the process now takes around 18 months for models of cars whose designs the company has worked on in the past. (There are future plans for a California Spyder.) And while Lyon admits that they will always have to source tires and carburetor that cannot be made in-house, thousands of pieces are individually crafted in Reading — even those that make up features that perhaps weren’t around in the ’50s and ’60s.

“We never try and pass one of our cars off as an original car,” Lyon said. “We’re making the perfect copy, but it is a copy.”

Air conditioning, for example, is one such request that GTO Engineering is often asked to add to their Ferraris, keeping it hidden to be true to the original design, while newer electrical parts also improve reliability. The 250 GTO commissioned by Manhattan Motorcars has an engine that is half a litre more powerful than the original.

GTO Engineering also ensures that every vehicle it builds has a unique I.D. number and paperwork that is tied to an original Ferrari —even if their starting point is what remains of a car that’s been burnt out or had numerous parts stolen off it and nothing more. “We’re not destroying any cars,” said Lyon, who added it’s preferable if the model whose I.D. they are working with is older but not essential. “We don’t need any parts; we’ve got all the parts… We like to have something physical if we can — so, a bit of chassis, or some parts, if possible. But we basically make the car.”

For that reason, Marcel Massini, the Ferrari expert, estimates that while there were only 165 SWB Berlinettas created from 1959 to 1962, as many as 300 or more additional versions with Ferrari I.D.s could have been built by companies similar to GTO Engineering, who operate in a market that includes those working on replica Jaguar E-Types and vintage Porsches.

This has split opinions in the car collecting world. Massini, a purist, has called the use of I.D. numbers tied to perhaps more mass-produced Ferraris “sacrilege” and says it’s a shame that “other Ferraris are being butchered and basically killed to use their identities or their remnants to build a 250 SWB replica.” Others see it as a cheaper alternative to have access to a design of Ferrari that otherwise remains out of reach — like a classic painting purchased for an exorbitant fee and then locked away in a private collection, and not shared with the public.

Miles Miller, the chief operating officer of Manhattan Motorcars, while sympathetic towards the views of Massini and others, said the focus should simply be on the craftsmanship itself. Miller was not intending to commission such a car when he visited GTO Engineering around two years ago, but having been impressed by the performance and build quality, he and his father, Brian, who owns the business, saw a car that they believe could offer a weekend drive for those who cannot get their hands on the original — or even a daily drive for someone who does not want to damage their own rare Berlinetta itself.

“There’s always going to be people who poo poo it a little bit because it’s not original and everything like that. It’s still a beautiful piece of engineering; it’s stunning to look at; it sounds great — so don’t over complicate it.”

Lyon, naturally, agrees. “There are some people who don’t like it, but most people say, ‘I can see why they’re doing that — that does make a lot of sense,” he said. “You don’t want to use something that’s very unique and irreplaceable; you want something you can use and have fun in. Not many people use the original cars anymore — which is very sad, but it’s true.” Lyon hopes to hear the sound and see the sight of a new GTO out and about soon.”