Using the Past to Shape a Future

Maria Kreyn’s Newest Permanent Installation in London

WRITTEN BY April Richon Jacobs

December 16, 2021

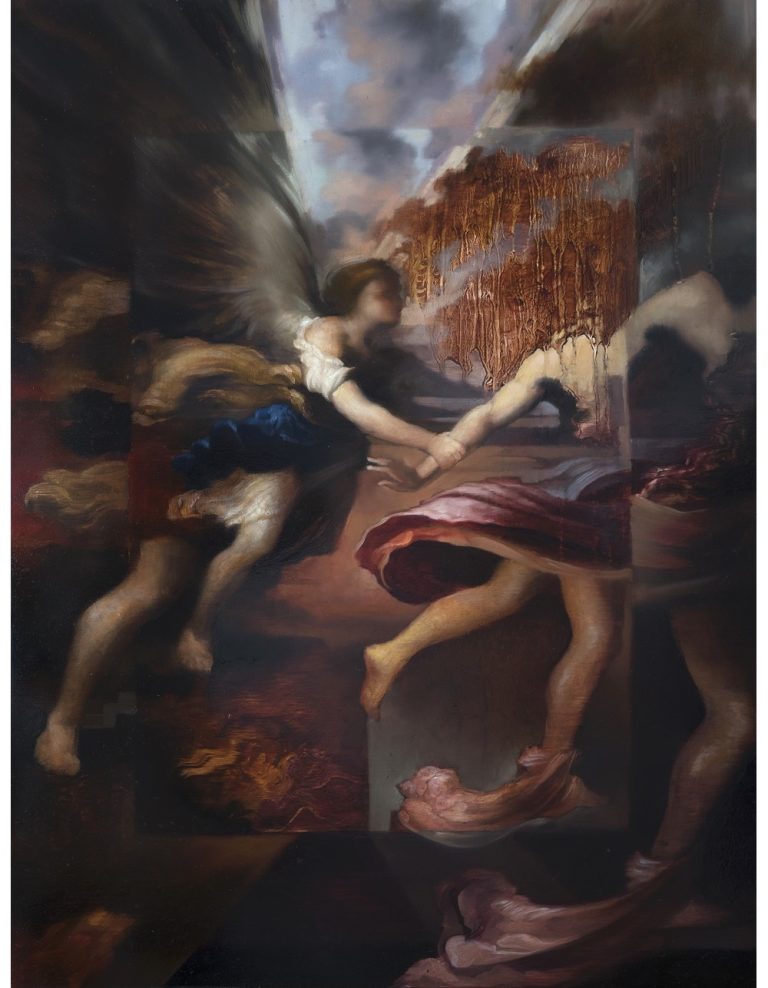

Brooklyn-based painter Maria Kreyn reflects on her epic cycle of paintings for the newly restored Drury Lane Theatre in London, commissioned by Andrew Lloyd Weber with the works of Shakespeare as its theme.

“Maria, let’s do Shakespeare; I’d like you to make this work dangerous and apocalyptic — with your soul on the line.” Such was the directive issued by none other than Andrew Lloyd Weber to the artist Maria Kreyn, in a request that would leave most artists weak in the knees. Not so with Kreyn, who spent the better part of the pandemic lockdown doing a deep dive into the complete works of Shakespeare. She even worked with the acclaimed British scholar Trevor Nunn, who is said to be the only person alive to have directed all 39 of Shakespeare’s plays. Kreyn’s epic cycle of paintings is now complete, with all eight of these lush, breathtaking paintings recently installed in London’s Drury Lane Theatre. The project was part of a three-year long, $82 million renovation overseen by Andrew Lloyd Weber, who purchased the venue 44 years ago.

Maria Kreyn paints with the Old Masters in mind, creating work on a massive scale rendered in sumptuous jewel tones that highlight the emotional intensity of her softly-painted figures, who are often nude or partially draped in silky fabrics. Her work was a natural fit for Lloyd Weber, who reached out to Kreyn after seeing her work in Vanity Fair. When he initially phoned her studio, she didn’t quite believe it was him at first. But eventually the two fell into a natural collaboration. She recounts, “I came out to London and I saw it when it was just a construction site, very raw, very bare bones. It was really exciting –- you could tell that something utterly extraordinary was going to happen.”

Love, madness, tragedy, ecstasy, despair –- how does an artist convey the greatest themes of the human condition? Much of what Kreyn is able to express in her paintings, which are largely realist but executed with a soft, dripping brush, comes from the merest gesture. An outstretched hand or a graceful twist of the wrist can elicit desire, longing or even madness. Kreyn even paints herself into her own work, using her own nude body as model. “It’s literally about finding the articulation and the gestures and the choreography,” Kreyn explains. “It’s kind of like a director’s project, but I’m not coming up with a play, I’m coming up with one ‘snap’ or one image that gives the emotional thrust of the whole play at large as I felt it.”

Kreyn herself is somewhat of a renegade. As the child of Russian émigré parents (her

mother is a classical pianist), she studied philosophy and math at the University of Chicago, but

left after two years. She never participated in a traditional MFA painting program, but chose

instead to apprentice with a European painter in Norway. Her paintings reach deep into the archives of art history –– you will find aspects of Goya and Zurburán in her work, and a bit of

Bacon’s melting, dissolving forms.

In tackling Shakespeare, Kreyn found universal themes that continue to resonate, especially in the present day. For her latest body of work, Kreyn has amped up those big themes, zooming out into great walls of clouds and pouring torrents of rain. These new paintings pay homage to The Tempest but have eliminated the human figure altogether, choosing instead to revel in the tumultuous glory of the weather in all its mercurial moods. She elaborates, “It’s the type of work that I’ve been wanting to do for a really long time. Rather than focusing on the human form directly, I’ve been thinking about the human experience and the human drama from a different vantage point, where you don’t even see the humans anymore.”

Despite their ties to Art History, Kreyn’s paintings are resolutely contemporary. They speak to a certain present zeitgeist. “When you’re making work, the idea is you want to be constantly challenged beyond what you think you can accomplish,” she remarked. “These paintings are a conversation with Shakespeare, not an illustration. It’s this deep dive into the human condition and psyche — into the big themes of life that still capture us centuries later.”