Crisis Management

What we can learn from Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton’s failed mission to Antarctica

WRITTEN BY DANIEL HILPERT

IMagery Courtesy of the Royal Geographic SoCiety and Public Domain

MAY 29, 2020

Humankind is facing the biggest crisis of our generation. The decisions that governments and people make now will shape our world for years to come. When we take a moment to look back, history shows us that the ability to act quickly, intelligently, and decisively should be innate for great leaders. The explorer Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton, a heroic figure in the age of Antarctic exploration at the turn of the 20th century, is remembered in spite of his failed mission to Antarctica in 1914 which has become synonymous for crisis management and leadership.

Shackleton was the kind of leader our current governments and companies should strive to be. Today, during the COVID-19 crisis, most world leaders were gripped with paralysis, unlike Shackleton who boldly embraced his leadership role, forged unity among his crew and overcame unrest, mutiny and against all odds defied death.

The year is 1902. Teddy Roosevelt is president, the Ford Motor Company produces its first car and the race to discover the South Pole, the equivalent of the 1960s space race, is on in full force at a time when nationalism and patriotism are at their highest.

As the French philosopher and mathematician Blaise Pascal observed in a quote as relevant now as in 1902, “The sole cause of man’s unhappiness is that he cannot stay quietly in his room.” Shackleton embarks on his first expedition to the South Pole. The voyage goes terribly wrong and Shackleton and his men have to turn around. Shackleton begins planning for a second expedition the very moment he returns. It is at this time that one of his management principles is manifested: make your decisions and stick with them. Don’t try to make everyone happy. Also, make sure you have adequate food supplies.

1907, his second expedition fails and he gears up to return again.

1914, a third attempt on the eve of The Great War. This is when Shackleton’s skills as entrepreneur are exemplified—he raises money, he hires a team based on experience, aptitude, attitude and ability to work together as a finely tuned unit.

Shackleton sets out in August 1914 for South America and makes it to the coast of Antarctica by late January 1915. Eighty miles off the coast, his ship is locked in by icebergs and the only option is to wait for the ice to break. As days become weeks and weeks become months, the journey turns even more harrowing when the ship, under pressure from the expanding icepack, is compromised and sinks. For almost six months they live on the ice in lifeboats turned into tents under freezing temperatures.

At the moment of greatest distress, the men start doubting they will survive the freezing temperatures and declining food supplies, and they start fighting. But Shackleton seizes the moment and pivots. He knows he has to give his men the impression that they can do better and come out on the other side alive.

How does Shackleton keep his crew motivated? He shows up every day with a mission. He looks confident and he carries himself carefully. He doesn’t show doubt or anxiety. This conveys that he cares and that together they will get home safely. He understands that routine is incredibly important to create stability and confidence—so he implements duty roster every day. The routine also includes plays, games, presentations and camaraderie. Above all, Shackleton demonstrates empathy.

Leaders need the ability to look forward during volatile and transformative situations. In this high stakes scenario, Shackleton is calculating how to keep them alive. It is essential to learn from mistakes, but true leaders also own their mistakes and quickly assimilate them. In a crisis it’s critical to keep moving forward.

Shackleton applied his own secret sauce when mutiny seemed imminent. We see this knowledge translated to modern times when the boss makes each member of the team believe “we can do this.” Great leaders help us accomplish better and harder outcomes together than we can get ourselves to do on our own. Shackleton held frequent meetings with the group and individual one on ones with his 27 men. He made a point to connect with each person on a regular basis. Many managers rise to the top job but cannot sustain it because they lack the inner fundamentals. True leaders teach us that being present is critical and personal. It’s part of their identity. It’s what fuels them.

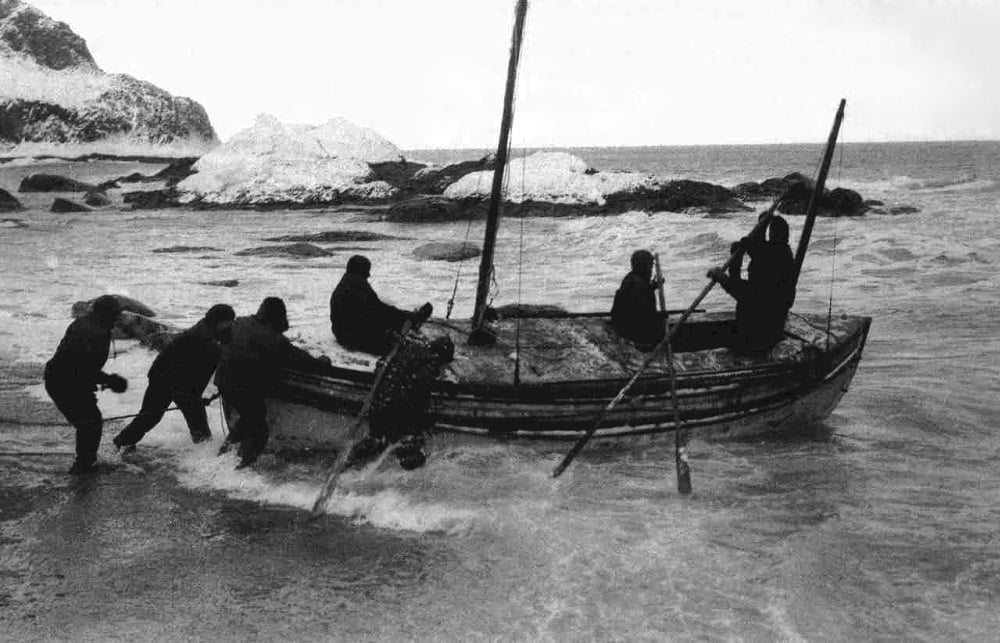

Finally, after drifting on the ice for months, Shackleton and his men spot Clarence Island. They have three lifeboats. The decision is made to sail for land, and land on the nearby Elephant Island. Even after this dangerous journey, Shackleton, knowing shipping lanes are not nearby and rescue is unlikely, decides to take one of the lifeboats on the 800+ mile trip to a whaling station. He does this despite warnings that there is much ice to the north. He and five men head in the lifeboat converted to sailboat. This journey is worse than the last. A storm erupts sinking a 500-ton ship in nearby waters. Huge weather obstacles continue but somehow they make it to the island. They then walk through dangerous, mountainous terrain finally making it to the whaling station.

But still they are not done. Shackleton needs to procure a ship to get back to pick up his 23 remaining men on Elephant Island. He has a deadline as well, he has instructed his men that if he does not return, they are to undertake their own dangerous attempt to gain safety. His rescue attempt is thwarted three times by sea ice, the boat turns around because the icebergs threaten.

It’s August 1916. In a Chilean tugboat Shackleton finally rescues his men, they make it home to England in May 2017, a completely different world. Millions have died in the ongoing war. After the war, Shackleton finds himself heavily in debt, but he is able to travel to America where he gets on the speaking circuit. Later, back in England, he hatches plans to return to Antarctica. When he reaches out to the old crew, they do not hesitate to sign up again, some having not been paid for the last expedition.

What can we learn from Shackleton and the person he became during a series of very turbulent situations? The lesson here is that great leaders are made in adversity and not born.

Humankind is in the midst of a global crisis. The decisions our leaders and governments take will shape the world for years to come. They affect not just our healthcare system, but also our economy, politics, livelihood, and culture. Like Shackleton, decisive action with the interests of all at heart is the key. We should also take into account the long-term consequences of our actions, and plan for contingencies in case what we hope for does not come to be. When choosing between alternatives, we should ask ourselves not only how do we overcome the immediate threat, but also what kind of world we will inhabit once the hardship passes.